Behind the scenes: Co-authoring a cookbook

The unlikely intersection of Ireland, India and Illinois

Ireland, India, Illinois. It’s the unlikeliest of intersections.

I grew up in Illinois and moved to Ireland in 1999.

One year later, Sunil Ghai moved here too from India.

Twenty-three years after that, we wrote Spice Box together, the first Indian cookbook published in Ireland.

The book reflects what I’m constantly banging on about: that Ireland has a vibrant, diverse and world-class food culture, with talented people cooking and producing food every bit as good as – and sometimes better than – the food in major world cities like London or New York.

Case in point? Sunil has been named Best Chef in Ireland, not once but twice. And not best Indian chef (although he’s won awards for best world cuisine too) – best chef, full stop.

The path to getting Spice Box published wasn’t straight or smooth. It started way back in 2017 via a bit of match-making but we got sidelined by two new restaurant openings. It took the forced slowdown during the pandemic lockdowns to finally get it off the ground.

The match-maker

Darina Allen from the Ballymaloe Cookery School had been badgering Sunil for years to write a cookbook by the time she introduced us at the last Ballymaloe LitFest in 2017.

Darina and I knew each other from my work editing the new edition of her cookbook A Simply Delicious Christmas in 2014 and because I had also just co-authored a cookbook with her son-in-law, Philip Dennhardt, all about pizza.1

But she had been a fan of Sunil’s food long before that. As she writes in the foreword to the book:

My first taste of Sunil’s food when he was cooking in Ananda in Dundrum in the early 2000s stopped me mid-sentence. I was curious – who exactly was the chef behind these delicious flavours? Then Sunil Ghai emerged from the kitchen.

Over and over again, I encouraged Sunil to write a book to share his cooking, not just with his many devotees but with a wider audience who would love to be able to cook authentic Indian food, particularly the kind of home cooking often with a contemporary twist that Sunil and his team serve at his restaurants Pickle and Street in Dublin and Tiffin in his adopted town of Greystones.

For the next three years, Sunil and I worked on the book in fits and starts before Sunil got pulled away by opening his second and third restaurants, Tiffin and Street. And then, well, I don’t need to tell you what happened in 2020.

Cooking the book

With the forced restaurant closures and strict lockdowns in Ireland, we both finally had time to prioritise the book.

We put together the concept (more on that below), the table of contents and some sample recipes and sold the book to Penguin Sandycove in December 2020 (just a few months before I started my own publishing house).

During the summer of 2021, when restrictions had eased, I would drive from Co. Louth to Greystones, Co. Wicklow once a week on a day when Tiffin was closed so that we could take over the kitchen there to cook our way through the book.

Standing out of the way at the corner of the stove, I would scribble down Sunil’s recipes as fast as I could while he blitzed through eight, ten or twelve recipes in four or five hours. Sometimes we’d have so many different pots of curry on the go that I would lose track of what was what.

And yet Sunil never once consulted any written recipe of his own.

He would taste each dish at various stages, sometimes increasing the amount of salt or a spice by a quarter or half a teaspoon or saying we needed to make a note to reduce the amount he’d originally put in. Even though multiple spices are used in all his recipes, he would know if just one of them wasn’t quite right purely from his taste memory.

Sunil is also one of those chefs who cooks entirely by eye and instinct – he never measures or weighs anything.

He had to buy measuring spoons, a scale and a measuring jug just for this book. Sunil’s recipes use a lot of water (rather than, say, stock) and I was forever having to ask him how many millilitres he had just added to a bubbling pot.

As Darina writes in the foreword after I’d told her about our recipe-writing process, I ‘chased Sunil around the busy kitchen, standing between him and the scales to capture his spontaneous cooking’.

Those trips to Greystones were just the start.

Over the next six months, I typed up all my shorthand notes and made every single recipe again in my own home kitchen, both as a way to double check my notes but also to make sure they worked in a logical way for a home cook.

An advantage of testing all the recipes in the Tiffin restaurant kitchen was that Sunil always had two of his chefs helping that day, so we had a steady supply of pre-chopped veg, prepared meats or liquids that had already been measured out.

But that also meant that sometimes the order in which we’d cooked elements of a dish in the restaurant kitchen didn’t work as well for a home cook without a sous chef, so it had to be tweaked.

Making the recipes myself also revealed three important things that I wouldn’t have realised otherwise: that mise en place is the key to cooking Sunil’s food; that there is an underlying formula at work in the curry recipes in particular; and that we could incorporate both of these points into the layout of the recipes themselves.

The life-changing magic of mise en place

The way I usually cook, I’ll get onions or veg sauteing while I prep the rest of the ingredients, but that just wasn’t working with Sunil’s recipes.

They aren’t difficult but there are a lot of spices to take down from the shelf and measure out or veg to chop, plus the various cooking stages tend to be fairly short – just a minute to temper the whole spices in hot oil before adding the onion, garlic and ginger and cooking those for only a few minutes more.

I was constantly feeling flustered and rushed, not to mention that the kitchen was always a mess. After making half a dozen recipes this way, it dawned on me that I needed to take a page out of the restaurant kitchen’s book.

Mise en place is a French term that means ‘to put in place’ or ‘to gather’. It basically means doing all your prep before you start cooking, similar to the way you should have all your stir-fry ingredients prepped and ready to go because everything cooks and comes together so quickly.

As we said in the ‘how to use this book’ section of the introduction:

Spend 10 minutes peeling and chopping the onions, ginger and garlic and measuring and preparing all the other ingredients before you begin to cook and you will be amazed at how quickly and easily the recipes come together, with plenty of time to clean up as you go. You can have a delicious homemade curry simmering on the hob and have the kitchen tidied up too by the time you sit down to dinner.

I promise you that prepping everything first will completely change your experience of cooking not just my recipes, but all your cooking. You can get inexpensive prep bowls from catering companies – try the Arcoroc range of chef bowls2 from Nisbets in Dublin, which come in different sizes that are stackable in your cupboard.

This one simple step completely transformed the way I cooked these recipes. I’m such a convert, I joke that ‘mise en place’ will be my next tattoo.

The curry formula

Once I’d made a few curries myself, I realised that most of them follow the same four steps:

1. Temper the whole spices in hot oil for 1 minute, just until fragrant or the whole seeds start to pop.

2. Cook the onions and fresh green chillies (if using) with the salt until softened (the salt helps to draw out the water in the onions), then add the ginger and garlic and cook for 1–2 minutes more, just until fragrant.

3. Add the protein and sauce ingredients, such as coconut milk, Greek yoghurt, tomato passata and/or water, and let the curry simmer to marry the flavours together. I use a lot of water in my recipes, not stock, as there is plenty of flavour from the other ingredients. I’ve put the water in bold in the recipes so that you don’t accidentally skip over or forget this vital ingredient.

4. Finish the dish with a final pinch of ground spice, fresh herbs, a knob of butter, a little cream and/or a squeeze of lemon juice.

Understanding these basic building blocks can make a recipe – or a new cuisine – less intimidating. If you can make a Bolognese sauce, you can make a curry.

The recipe layout

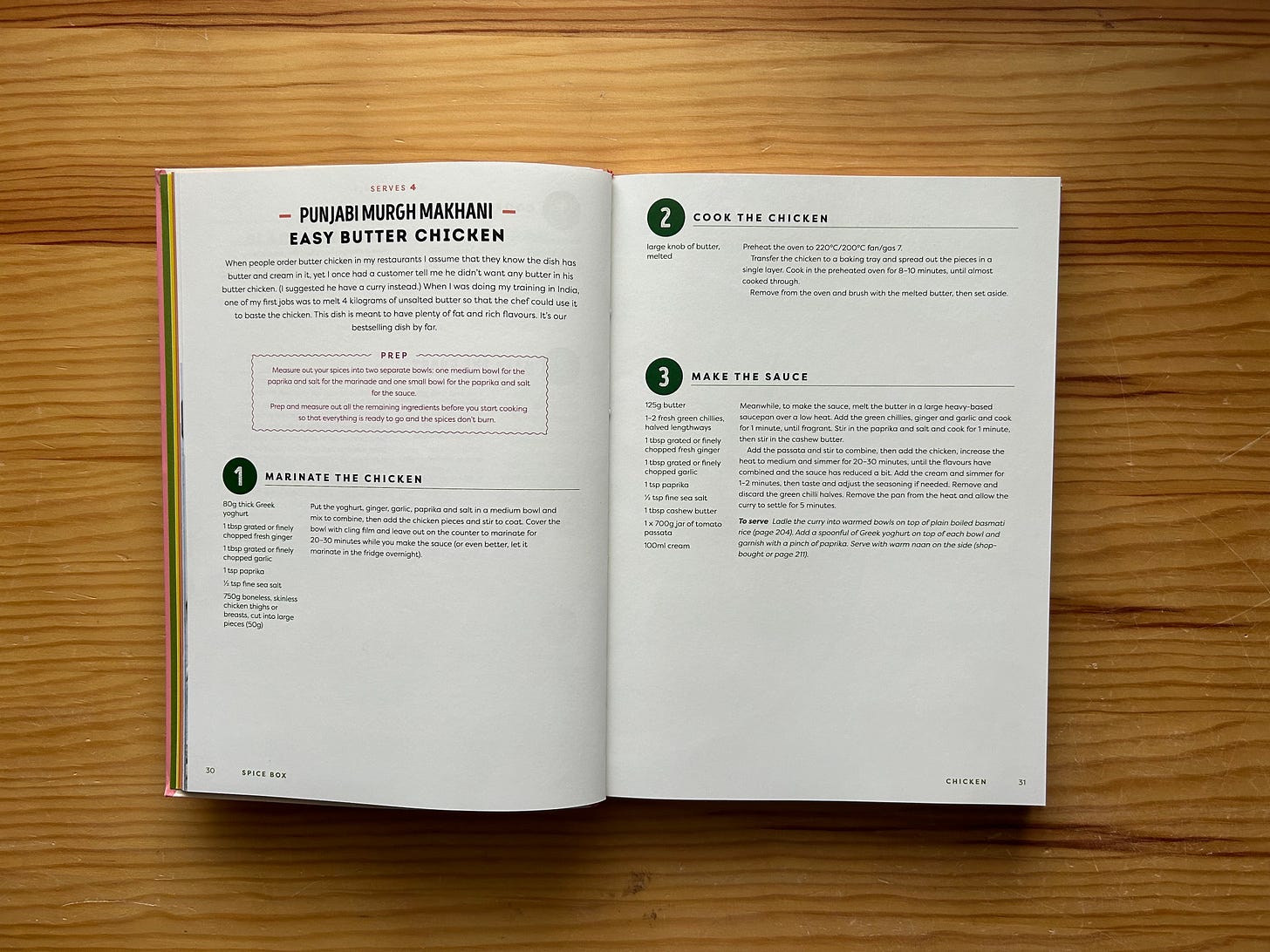

The mise en place and the curry formula then came together into the somewhat unconventional layout of the recipes in the book.

The mise en place is so important that those prep instructions are set off at the start of every recipe in a text box.

After seeing that the recipes were following a formula, I wanted to make this more obvious by baking it into the book design.

This is why the recipes are laid out the way they are in the book – you can see at a glance what the steps are and which ingredients belong with which step. This is also why your mise en place is so helpful and makes cooking these recipes so easy.

Editors are often nervous or wary of recipes that have long ingredient lists – the worry is they will be intimidating or offputting to readers. This was always going to be an issue with Spice Box because there are simply so many spices used. It takes only a moment to measure out spices but the optics of such long lists weren’t good.

Inspiration struck while I was reading the Julia Child issue of Cherry Bombe.

The layout of some of the recipes in the magazine mimics the way they appear in Mastering the Art of French Cooking, with the ingredients for each step set alongside the instructions for that step. This creates bigger gaps between certain steps than you would usually see in a layout, but it’s that very white space that makes it so much more intuitive and reader friendly.

The concept

All cookbooks are structured around a central theme or idea. In Spice Box, the hook is that all the recipes use common spices that you can find in any supermarket, which makes the book an accessible introduction to cooking Indian food.

I credit this concept for getting the book published but it was hard for Sunil at times, who prides himself on his authentic cooking, when he knew a recipe didn’t taste exactly as it should because we couldn’t use, say, black cardamom or Kashmiri chilli powder.

‘We have to bring readers along with you,’ I would say.

But Sunil knows this better than anyone:

When I moved to Ireland in 2000 there were already plenty of Indian restaurants here, so I visited as many as I could to see what was being offered. Why were people so obsessed with only lamb or chicken korma rather than a home-style chicken curry? Why were people eating only chicken breasts, not thighs? Why were people being served chicken tikka that was a strange, lurid beetroot colour rather than a chilli-red tandoori chicken on the bone?

Many people’s idea of Indian food has been based on the food they’ve been served in restaurants, but oftentimes that food has been altered to cater for Western tastes and is not a true representation of authentic Indian food. In my restaurants I’m trying to change that, but it took me and my team a long time to bring people along and help them understand what real Indian food should be.

Just like he did as a restaurateur, Sunil had to start with the basics as an author too. In the parlance of reality TV, it’s all part of the journey.

But people are more adventurous now in terms of what they’re willing to try and they also want to know more about the cuisine. When it gets to the point where someone becomes a regular and I know who’s eating in the restaurant based on the order that comes in time and time again, I’ll go out and talk to them and encourage them to try something new. And I very often change people’s minds, whether it’s getting them to try a different type of curry or even something they may never have had before, like my signature dish of goat on toast.

And now it’s over to you

Six years after she introduced Sunil and I in Cork, Darina Allen launched Spice Box at Sunil’s Pickle restaurant in Dublin in September. The book is out in the world at long last.

Throughout the entire process of writing the book, I had one goal: that when a reader cooks one of Sunil’s recipes, I want their reaction to be, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I made that!’

The best thing about the book’s core concept of using everyday spices is that it shows you how to use ingredients you may have been cooking with for years in new ways to get new flavours out of them that you wouldn’t have thought possible.

Indian food isn’t spicy – it’s full of spice. It’s not all about chillies and heat; it’s about building layers of flavour.

As Sunil says in the book, ‘I hope that I can encourage you, too, to cook something new using ingredients you’re already familiar with.’ After all, isn’t that the point of any cookbook?

Just don’t forget the mise en place.

Spice Box: Easy, Everyday Indian Food by Sunil Ghai is published by Penguin Sandycove.

To further prove my point about Ireland’s food scene, Philip is from Germany and moved to Ireland after he met and fell in love with Darina’s daughter, Emily, in New York. Who would have ever thought a fifth-generation German master butcher and an American writer would do a book all about pizza in Ireland? But that’s a story for another day.

Besides my favourite knife and chopping boards, those Arcoroc bowls have become the hardest-working equipment in my kitchen. I have the two smallest sizes and use them almost every day.

A lovely read Kristin! Yes to Mis en Place, and we do it without even clocking it, a bit like our use of approximations. Another thing to say is that the steps to a curry do change depending on where you're fro. Bengalis for instance will add a pinch of sugar to hot oil to caramelise it and add colour and a hint of sweetness to the curry. In the North, you don't just soften onions for a curry you get them to almost caramelise golden before adding further ingredients. The most important thing is to do additions in stages! Good luck to Sunil and you - a tremendous achievement!